Inclusive Climate Infrastructure: Turning Dialogue into Action – Climate Action!

Inclusive climate infrastructure means that the systems we build to adapt to climate change (energy, transport, green and blue spaces, communication networks) are planned and managed so that everyone, including people with disabilities, can use and benefit from them. It is not an add-on or a specialist track of climate action. It is about anticipating diverse needs from the outset and co-creating solutions with those most at risk.

Globally, 1.3 billion people, around 16% of the world’s population, live with a disability, and about 80% live in low- and middle-income countries (World Health Organization & World Bank, 2011). Many of these countries are also among the most climate-vulnerable (IPCC, 2022). Cities, where roughly half of disabled people live, produce around 70% of global emissions while facing intensifying heatwaves, floods, and storms (UN-Habitat, 2020). People with disabilities are disproportionately affected because they are twice as likely to be injured or die during disasters (UNDRR, 2015), more likely to live in informal settlements exposed to environmental risks (World Bank, 2021), and often excluded from evacuation planning and climate communication (GDIHub,2024). Interruptions to power and transport systems can cut off access to healthcare, assistive technology, or safe shelter. Without inclusive planning, climate adaptation risks leaving behind those who most need protection.

At New York Climate Action Week, we wanted to spark more thought on this subject by trying out a new session format. Too often, panel discussions fall into pre-planned presentations, with little space for real problem discussion. We set out to change that by making the session itself a brainstorming exercise: persons with lived experience would set the challenge live, and panelists would have to respond in real time. The aim was to move away from a static dialogue and instead spark practical, solution-focused discussion.

How it worked

We structured the session around two “design challenges,” covering ‘Inclusive Energy Access’ and ‘Inclusive Urban Mobility.’

In the first challenge, Tamir from Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, described what it means to live with a disability in one of the world’s coldest capitals. He relies on an electric wheelchair, an adjustable bed, and a computer for work, devices that become unusable when the power goes out. Frequent outages restrict his independence: if electricity fails while he is at home, he cannot leave; if it happens when he is outside, he cannot return safely.

But Tamir also pointed to the wider picture. Around half of Ulaanbaatar’s 1.6 million residents live in ger districts, areas not connected to the city’s central heating system. To keep warm, households burn coal or wood in small stoves, creating severe indoor and outdoor air pollution, as well as high fire risks. For people with disabilities, especially those with limited mobility or visual impairments, lighting and maintaining fires can be both difficult and dangerous. He emphasised that energy poverty in these areas is not just an economic issue; it can be a matter of survival.

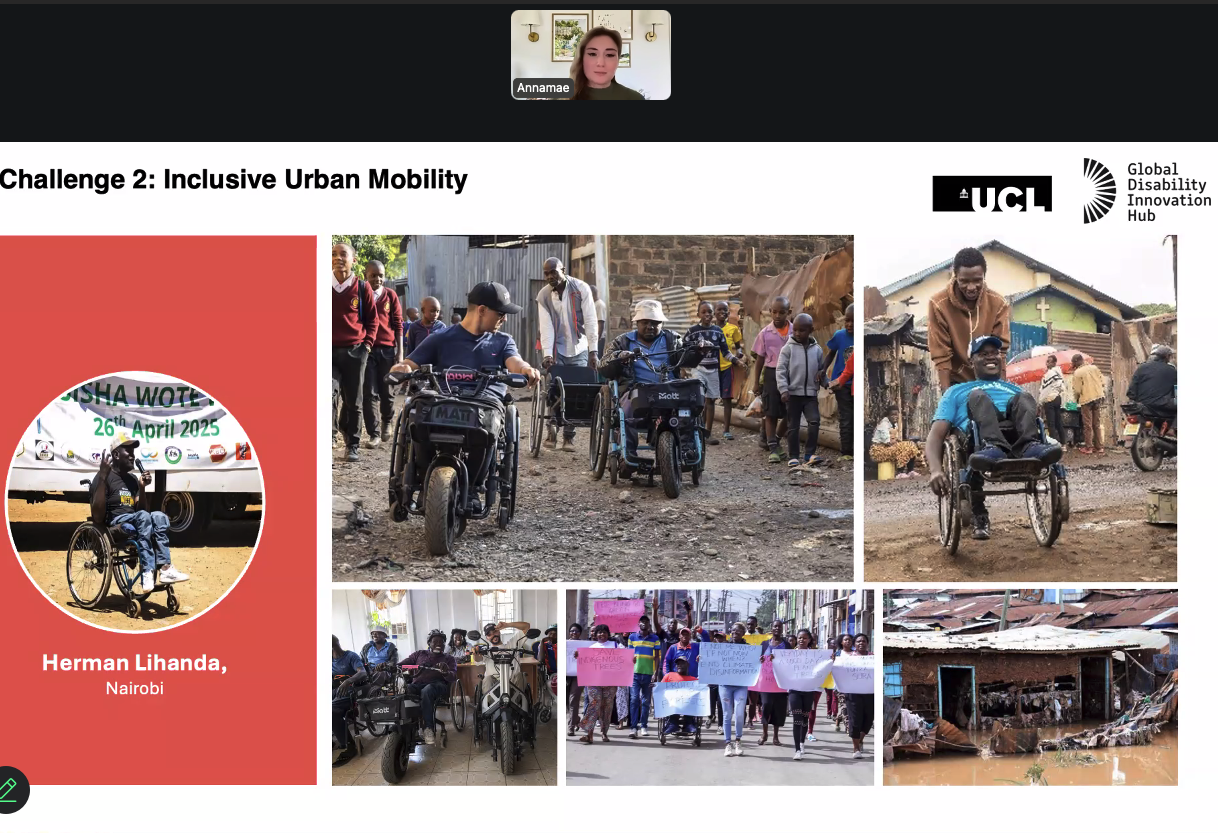

In the second, Herman from Nairobi, Kenya, spoke about everyday mobility in a dense informal settlement. Cracked pavements, open drains, flooding, unreliable minibuses with steep steps, and extreme heat all combine to make moving around a daily obstacle course. He asked a direct question: what simple, affordable measures could make existing public transport and infrastructure more usable, and how can communities most affected by climate issues shape the solutions?

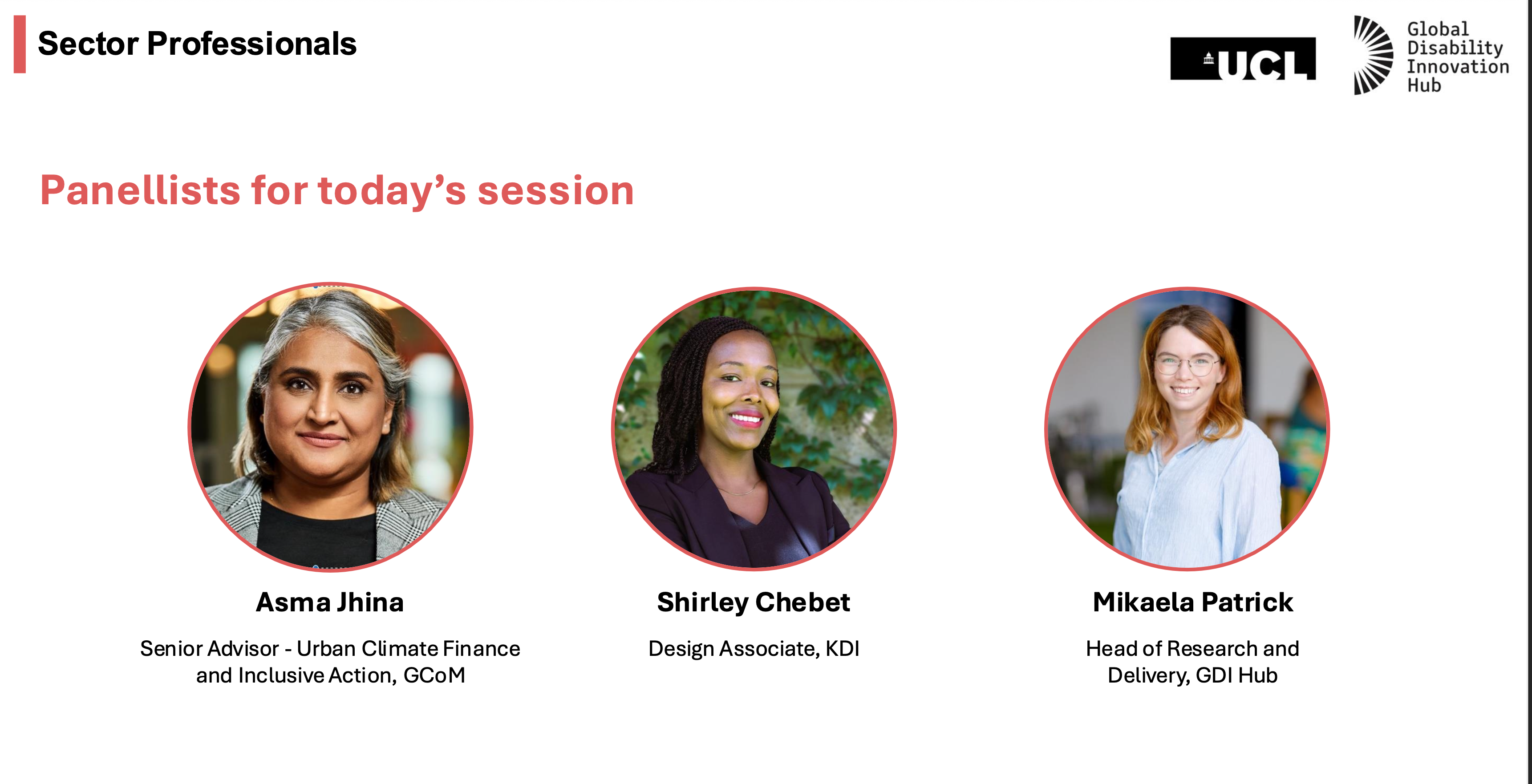

We were also joined by three sector professionals:

- Asma Jhina, Senior Advisor, Urban Climate Finance and Inclusive Action, Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy

- Mikaela Patrick, Head of Research and Delivery, GDI Hub

- Shirley Chebet, Design Associate, Kounkuey Design Initiative

They brought together expertise in inclusive design, climate action, and urban design. The challenges were not shared with the panellists beforehand. This meant that by hearing the challenges live alongside the audience responses were rooted in immediate reflection, co-creation, and practical next steps.

What we learned

Across the climate space, whatever sector or area we are trying to work in, we need to be co-creating solutions with the people who are likely experiencing the most exclusion, such as people with disabilities.

- Mikaela Patrick, Head of Research and Delivery, GDI Hub

Several strong themes emerged from this trial format:

- Energy and assistive technology must be planned together. For people who rely on powered devices, outages or unaffordable energy costs are life-changing. Utilities and governments need .to integrate undisrupted power supply and accessible energy services as part of resilience planning.

- Small, rapid interventions matter. Intermediate infrastructure solutions, shaded bus shelters, driver training, and better drainage may seem modest, but they open up daily mobility, independent living and safety for thousands.

- Community stewardship is an untapped resource. Small grassroots organisations and communities are working to find context relevant inclusive climate solutions and should be empowered not only to benefit their communities but to scale up the good practices derived from their work.

- Finance follows evidence. Demonstrating how inclusive infrastructure improves jobs, health, safety, and wider socio-economic outcomes shall strengthen the case for inclusive climate finance pathways

Local authorities [particularly, in the Global South] are going to be the biggest employers and biggest procurers in the smaller cities. There is an opportunity to have policies in place, where you can build it [disability inclusion] into the whole project life cycle for infrastructure from concept through to implementation.

- Asma Jhina, Senior Advisor, Urban Climate Finance and Inclusive Action, Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy

Why this matters

This experiment in format reinforced a larger truth: inclusion cannot be reduced to a checklist. It is a systems issue. Climate infrastructure only becomes resilient when people who face the steepest barriers can use it, and when their knowledge actively shapes its design. By treating lived experience as the starting point, not the end-user test, we open up new ways to imagine and implement solutions.

Cities need to institutionalise co-design, so that people with disabilities are involved in co-designing public spaces. By using experimental methods [transit walks, site models, and maps] in Master Planning or planning for public spaces, we can identify some of those things that may not show up in drawings.

- Shirley Chebet, Design Associate, Kounkuey Design Initiative

A call for examples

GDI Hub is now gathering examples of inclusive climate infrastructure in action from local community-led initiatives to city-wide programmes. We want to learn from projects that have improved climate resilience and widened access, so that we can build an evidence base of what works and share it with practitioners and policymakers globally.

If you’ve worked on, seen, or evaluated a project that belongs in this space, please share it with us: a.muldowney@ucl.ac.uk

Together, we can ensure that as cities and systems adapt to climate change, they do so inclusively so no one is left behind.